Crime and Punishment: UTM prof studies early American prisons

U of T Mississauga assistant professor Ashley Rubin has been fascinated with prisons since her undergraduate years. Rubin, who joined UTM’s Department of Sociology in 2016, studies the evolution of penal systems in America and England from the seventeenth century through the early twentieth century, with a focus on the societal factors that create changes in penal practices.

“I want to understand why we do the things we do,” she says. “Why does punishment take a particular form, and how do those ideas spread?”

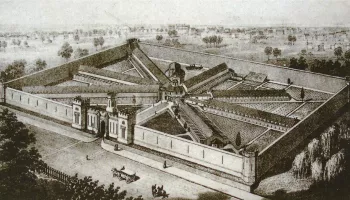

She is currently completing a study of Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary. The prison, which operated from 1829 to 1971, housed between 200 to 300 prisoners for a variety of crimes including: larceny; burglary; rape; manslaughter; second-degree murder; counterfeiting; and property offences (including horse theft). While the facility is notorious for famous inmate and mobster Al Capone, it has a more important place in American penal history for its unique approach to prisoner treatment and rehabilitation. As part of the Pennsylvania prison system, Eastern State provided an alternative to other approaches to prisoner housing and treatment.

The Pennsylvania prison system set out to revolutionize punishment, with a focus on penitence and “separate confinement,” where prisoners were isolated from other inmates. The facility was technologically advanced for its time, with central heating, flush toilets and showers in each cell, even before such luxuries appeared in the White House. Each prisoner also had access to a private yard for fresh air and exercise.

“The administration didn’t want prisoners to be stigmatized by their time in prison,” Rubin says. “Prisoner privacy was highly regarded, and they were hooded on their way to cells so they wouldn’t be recognized by anyone.” Rehabilitation was another important element. “Prisoners would have a loom or workbench, and would work at shoe making or weaving in their cells and could earn a very good wage.” Upon release, prisoners would receive gifts of clothes and money, and arrangements for post-incarceration employment. “Overall, their conditions were better,” Rubin says. “Some even asked to stay on after their sentences ended.”

“They wanted prisoners to succeed, as something that was important for society. They thought crime would kill the American republic,” Rubin says. “The Philadelphia system violated the idea that people in prison should be worse off than the lowest person in society.”

The Eastern State model was imitated across Europe, but was deauthorized the United States around 1913. Overcrowding and changing attitudes toward punishment saw the system supplanted by the Auburn prison system from New York state, a penal philosophy that required stripe-clad prisoners to perform group labour during the day and spend the night in solitary confinement, all under enforced silence. “The prisons at the time were often run by contractors, with a focus on making a profit off prisoner labour,” Rubin says. “Auburn has more in common with current prison practices.“

“Today, we don’t care about prisoner privacy and, in recent decades, the penal focus has been to ensure that prisoners don’t do well,” Rubin says. “There are longer sentences and it’s easier for people to violate parole conditions.”

“The prison system is only about 250 years old, and the idea of penal incarceration as punishment is still fairly new,” Rubin says. “What we do now is not what we’ve always done.”